When Kate Trinajstic told her mother that she wanted to become an Egyptologist, the response was ‘Don’t be ridiculous – you can either go to Secretarial College or Nursing School.’ Kate chose nursing, which although a rewarding career, did not fulfill her intrinsic curiosity for research; she completed a degree in Biology, PhD in Geology and has become an accomplished Paleontologist, currently an Associate Professor at Curtin University. Kate opened her talk by describing how Paleontology provides a vehicle for school students to integrate multiple strands of the sciences: Geology, Biology, Ecology and Chemistry, toward an understanding of factors that underlie the modern biosphere and to provide unexpected insights into sexual reproduction, human development and disease. During the 90s, traditional Paleontology – the detailed study of the structure of fossils as a window to evolution, was considered superseded by new technologies such as analysis of ancient DNA. However, modern techniques in imaging have enabled surprising discoveries by revealing hitherto hidden features preserved in fossils.

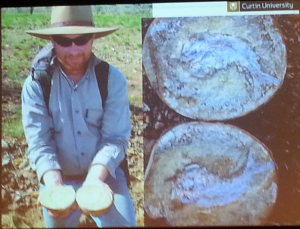

The Kimberley Reef Deposits (Gogo Formation), not formed by coral but rather sponges and stromatolites, provide a complete fossilized ecology. A common fossil of this region comprises rock nodules encasing ancient fish with bony skin armour – the Placoderms.

A ‘Life on Earth’ documentary helped to stimulate interest in researching the area by the Australian Research Council and, in his honour, the research team including Dr. Trinajstic named one of their discoveries Materpiscis attenboroughi – The ‘Attenborough Motherfish‘ Museum of Victoria ; David Attenborough Youtube clip. This fossil was significant via the preservation of an intact embryo – complete with umbilical cord – thereby comprising the earliest known occurrence of live birth in vertebrates, 375 million years ago. Subsequent studies have confirmed such findings in other Placoderms and stimulated re-assessment of previously misinterpreted structures which actually comprise embryos, rather than a fossilized fish dinner. Following the unequivocal demonstration of preserved soft tissue of the umbilical cord, previous disbelieved interpretations of fossilized muscle fibres, tendons and other soft tissue, became credible. Unfortunately, traditional methods for dissolving away encasing rock from a fossil almost always resulted in destruction of soft tissue features, but armed with modern imaging techniques of ‘microtomography’ via high energy X-rays and a dedicated beam of the Australian Synchrotron , Dr. Trinajstic and colleagues were able to observe structures deep within intact fossils and build detailed anatomical maps including muscle groups and attachment of tendons. The combined discoveries of live birth ( 200 million years earlier than previously thought), paired claspers of the male for mating and of compartmentalised musculature, revealed that the prehistoric Placoderms had actually evolved complex structures and behaviours (required for sexual reproduction with internal fertilisation) long before their recurrence in the evolution of modern vertebrates.

Paleontology not only reveals secrets of ancient evolution, but may also provide insights into human disease. Using a combination of structural features from Placoderm fossils and observation of embryonic development in the Elephant fish, Dr. Trinajstic and colleagues have sought to understand development features of fish relating to fusion of cervical vertebrae which mimic a condition in humans which dramatically restricts cervical spine mobility. The findings, consistent across hundreds of millions of years of evolution, suggest a developmental abnormality of soft tissue, resulting in ossification, rather than lack of proper segmentation of the vertebrae at a earlier stage of embryonic development. Armed with this knowledge, research into the underlying cause and potential therapy for the rare human disease may focus upon dysregulation of soft-tissue. Far from being a defunct arm of the sciences, with the benefit of modern technology, Paleontology will continue to challenge and refine current hypotheses of prehistoric ecosystems and the evolution of modern plants and animals – the Truth is In There, if you take a detailed look.